Raising the social media age to 16: a GP and mum’s perspective

As a GP, I spend much of my working life talking about anxiety, sleep problems, low mood and self-esteem. As a mum, I worry about many of the same things, but with an added and very modern layer of concern.

Legislation to ban social media for under 16s could come into force by the end of the year

Increasingly, these conversations come back to the same issue. Smartphones, social media, and the growing pressure on children to be online long before their brains are ready. This also starts with us as adults. As parents, the way we use phones and screens around our children matters. Children learn behaviours long before they understand rules, and what we model at home often shapes what feels normal to them.

That is why the UK government’s consideration of raising the minimum age for social media to 16 feels like a significant and overdue step. The proposal to raise the social media age to 16 is now under active parliamentary discussion. It is not law yet, but it is closer than ever. If agreed, legislation could follow later this year, with phased implementation. This is the moment where evidence, professional insight and parental voices still matter.

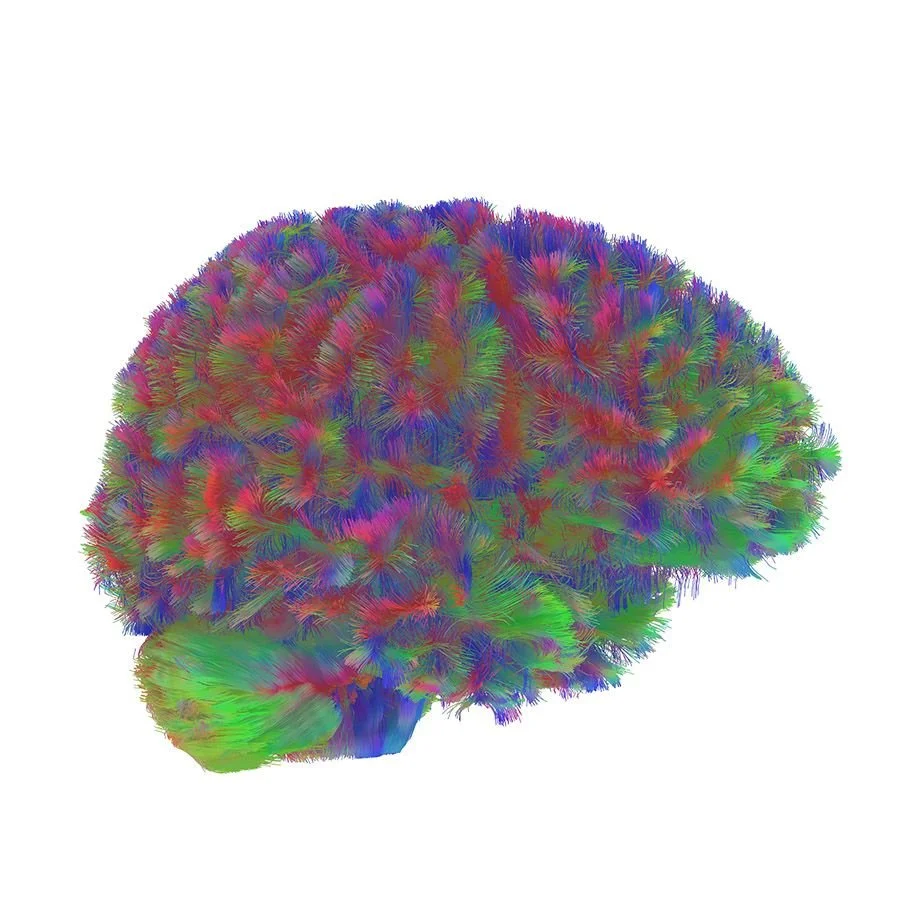

Children’s brains are still developing

From a medical perspective, childhood and adolescence are periods of rapid brain development. Areas responsible for impulse control, emotional regulation and risk assessment continue to mature well into the late teens and early twenties.

Childhood brain

This makes younger users more vulnerable to highly stimulating, reward-based digital environments. Social media platforms are intentionally designed to maximise attention and engagement. When these systems interact with an underdeveloped brain, the balance is not equal.

This is not about blame. It is about recognising biological vulnerability and designing safeguards accordingly.

The scale of early exposure in the UK

UK data shows how early this exposure now begins:

By the end of primary school, around 90 per cent of UK children own a mobile phone (UK Parliament Commons Library, 2024).

Around 60 per cent of children aged 8 to 12 are using social media platforms despite official minimum age rules (UK Parliament Commons Library, 2024).

Around one quarter of children aged 3 to 4 have access to a smartphone (UK Parliament Commons Library, 2024).

These figures make it clear that existing age limits are not being enforced in a meaningful way.

Mental health, cyberbullying and safeguarding risks

In clinical practice, I increasingly see children and teenagers affected by anxiety, low mood, sleep disturbance and school avoidance. While these problems are always multifactorial, online experiences are frequently part of the picture.

Cyberbullying does not stop at the school gate. Online harassment, social comparison and exposure to inappropriate content can follow a child home and persist around the clock.

UK organisations, including Ofcom and the UK Safer Internet Centre, report that significant numbers of children experience online harms, including contact from strangers, pressure to share images, and repeated bullying.

International bodies such as the World Health Organisation and UNICEF have also raised concerns about excessive screen use and online harm contributing to poorer mental well-being in young people.

Young people are not asking for more access

An important and often overlooked part of this debate is that many young people themselves express concern about the online world they are growing up in.

Research published by the British Standards Institution in 2025 found that nearly half of young people said they would prefer to have grown up without internet access during their teenage years. A majority also felt that technology companies prioritise profit over children’s well-being.

This should give policymakers and adults pause for thought.

Why raising the age supports families

One of the most common concerns raised about age limits is enforceability. Others worry that use will move underground.

From both a clinical and parental perspective, clear legal boundaries can be helpful. They create shared expectations, reduce pressure on parents to give in early, and make it easier for families to hold consistent boundaries together.

This is not about removing technology from young people altogether. It is about recognising that some environments are not developmentally appropriate for younger children.

We have seen similar shifts before. Behaviours once accepted were later regulated once evidence of harm became clear. Public health policy evolved accordingly. The same principle applies here.

A child development issue, not a political one

Raising the social media age to 16 should not be framed as a political or cultural battle. It is fundamentally about child development, safeguarding and mental health.

Children deserve time to develop identity, confidence and resilience offline before navigating algorithm-driven platforms that even many adults find challenging.

As a GP and a mum, I believe this proposal represents a proportionate, evidence-informed step in the right direction.

Short FAQ - what you might not know

Is this a complete ban on smartphones?

No. This discussion relates specifically to access to social media platforms. It does not mean removing phones, messaging, or the internet entirely.

What about enforcement?

No system will be perfect. However, clear legal standards make enforcement more feasible and reduce the burden on individual families to set boundaries in isolation.

What about vulnerable or marginalised young people?

Support and community are important. However, unregulated social media platforms also expose vulnerable young people to greater risk. Safer, moderated alternatives and offline support services remain essential.

Is this anti-technology?

No. Technology can bring many benefits. This is about age-appropriate use and safeguarding during key stages of brain development.

If we are serious about protecting children’s mental health and wellbeing, this is a conversation worth having now.