A closer look at the headlines linking diabetes drugs and aneurysm risk

You may have seen recent headlines suggesting that a commonly used diabetes drug could help save lives by slowing the growth of abdominal aortic aneurysms. As ever with medical news, it is worth pausing and looking beyond the headline to understand what the research is really telling us and what it does not yet mean for patients.

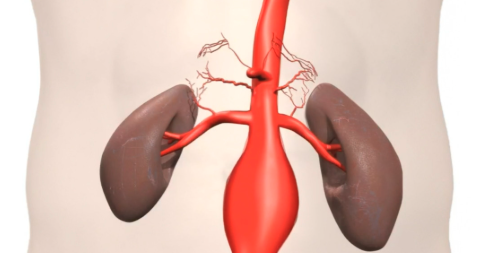

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA)

An abdominal aortic aneurysm, often shortened to AAA, is a swelling of the aorta, the large blood vessel that carries blood from the heart through the abdomen. Many aneurysms cause no symptoms at all and are picked up through routine screening. In England, men are offered a one-off ultrasound scan in the year they turn 65. If a small aneurysm is found, it is usually monitored over time.

Most aneurysms grow slowly. The concern is that if they reach a certain size, there is a risk they could rupture, which is a medical emergency. In the UK, abdominal aortic aneurysms are estimated to contribute to around 4,000 deaths each year, most commonly in older men.

At present, surgery is the main treatment once an aneurysm becomes large enough to pose a higher risk. There are no medicines that are routinely prescribed to slow aneurysm growth. That is why researchers are interested in whether existing drugs, already used safely for other conditions, might one day play a role.

The research behind these headlines focuses on metformin, a medication that has been used for many years to treat type 2 diabetes. Importantly, this research is not suggesting that people should start taking metformin to prevent or treat aneurysms. Instead, scientists are exploring whether some of the drug’s known effects could help us better understand how aneurysms develop.

Inflammation is thought to be one of the factors that weakens the wall of the aorta over time. Metformin is known to influence inflammation and metabolic processes in the body, which has led researchers to ask whether these effects might also be relevant to aneurysm growth. Early studies, including laboratory work and observational data, suggest this is worth exploring further.

It is essential to clearly define the limitations of this research. These findings do not prove that metformin prevents aneurysms from growing, and they do not change current medical advice. Results seen in early studies do not always translate into real-world benefit, which is why carefully designed clinical trials are needed before any conclusions can be drawn.

What this research does reinforce is a broader theme we see across many areas of medicine. Metabolic health matters. Conditions such as diabetes, high blood pressure and smoking are all known risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysms. Supporting cardiovascular and metabolic health through lifestyle measures remains the cornerstone of prevention and management.

For patients who have been diagnosed with a small aneurysm, regular monitoring and managing risk factors are key. For those invited for screening, attending that appointment can quite literally be lifesaving.

As a GP, I see research like this as encouraging, not because it offers an immediate new treatment, but because it deepens our understanding of how conditions develop and where future options might lie. For now, the most important steps remain early detection, good management of long-term conditions, and personalised advice from your own doctor.

If you have concerns about aneurysm risk, screening, or your cardiovascular health more broadly, a conversation with your GP is always the right place to start. Headlines can spark interest, but good care is always individual.

General information only. For personalised advice, speak to your GP or clinician.